Fancy some extra PC hardware, overclocking, gaming and modding content in your life this summer? You can get your hands on a FREE PDF download of each new Custom PC magazine issue released during May through to September.

You’ll find stuff like in-depth hardware reviews and step-by-step photo guides, as well as hard-hitting tech opinion, game reviews, and all manner of computer hobbyism goodness.

Our favourite regular feature is Retro Tech, so we’re sharing this latest one by Stuart Andrews to get you started on your summer of love with Custom PC.

Pity the poor PC of 1983-1984. It wasn’t the graphics powerhouse we know today. IBM’s machines and their clones might have been the talk of the business world, but they were stuck with text-only displays or low-definition bitmap graphics. The maximum colour graphics resolution was 320 x 200, with colours limited to four from a hard-wired palette of 16. Worse, three of those colours were cyan, brown and magenta, and half of them were just lighter variations of the other half.

By this point, IBM’s Color Graphics Adaptor (CGA) standard was looking embarrassing. Even home computers such as the Commodore 64 could display 16-colour graphics, and Apple was about to launch the Apple IIc, which could hit 560 x 192 with 16 colours. IBM had introduced the Monochrome Display Adaptor (MDA) standard, but this couldn’t dish out more pixels, only higher-resolution mono text.

Meanwhile, add-in-cards, such as the Hercules or Plantronics Colorplus, introduced higher resolutions, but did nothing for colour depth. The PC needed more, which IBM delivered with its updated 286 PC/AT system and the Enhanced Graphics Adaptor (EGA).

The new state of the art

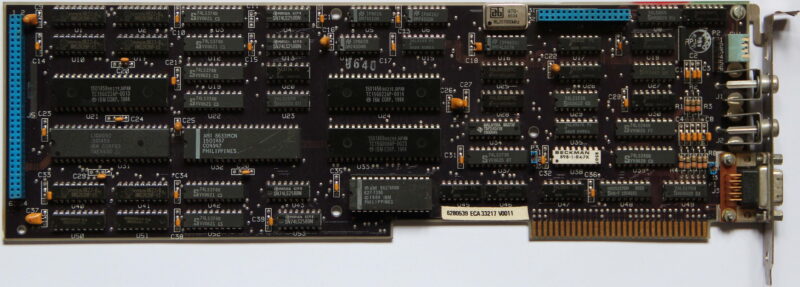

The original Enhanced Graphics Adaptor was a hefty optional add-in-card for the IBM PC/AT, using the standard 8-bit ISA bus and with support built into the new model’s motherboard. Previous IBM PCs required a ROM upgrade in order to support it.

It was massive, measuring over 13in long and containing dozens of specialist large scale integration (LSI chips), memory controllers, memory chips and crystal timers to keep it all running in sync. It came with 64KB of RAM on-board but could be upgraded through a Graphics Memory Expansion Card and an additional Memory Module Kit to up to 192KB. Crucially, these first EGA cards were designed to work with IBM’s 5154 Enhanced Color Display Monitor, while still being compatible with existing CGA and MDA displays. IBM managed this by using the same 9-pin D-Sub connector, and by fitting four DIP switches to the back of the card to select your monitor type.

EGA was a significant upgrade from low-res, four-colour CGA. With EGA, you could go up to 640 x 200 or even (gasp) 640 x 350. You could have 16 colours on the screen at once from a palette of 64. Where once even owners of 8-bit home computers would have laughed at the PC’s graphics capabilities, EGA and the 286 processor put the PC/AT back in the game.

Birth of an industry

However, EGA had one big problem; it was prohibitively expensive, even in an era when PCs were already astronomically expensive. The basic card cost over $500 US, and the Memory Expansion Card a further $199. Go for the full 192KB of RAM and you were looking at a total of nearly $1,000 (approximately £2,600 inc VAT in today’s money), making the EGA card the RTX 3090 of its day, and only slightly more readily available. What’s more, the monitor you needed to make the most of it cost a further $850 US. EGA was a rich enthusiast’s toy.

However, while the initial card was big and hideously complex, the basic design and all the tricky I/O stuff were relatively easy to work out. Within a year, a smaller company, Chips and Technologies of Milpitas, California, had designed an EGA-compatible graphics chipset. It consolidated and shrunk IBM’s extensive line-up of chips into a smaller number, which could fit on a smaller, cheaper board. The first C&T chipset launched in September 1985, and within a further two months, half a dozen companies had introduced EGA-compatible cards.

Other chip manufacturers developed their own clone chipsets and add-in-cards too, and by 1986, over two dozen manufacturers were selling EGA clone cards, claiming over 40 per cent of the early graphics add-in-card market. One, Array Technology Inc, would become better known as ATI, and later swallowed up by AMD. If you’re on the red team in the ongoing GPU war, that story starts here.

Changing games

EGA also had a profound impact on PC gaming. Of course, there were PC games before EGA, but many were text-based or built to work around the severe limitations of CGA. With EGA, there was scope to create striking and even beautiful PC games.

This didn’t happen overnight. The cost of 286 PCs, EGA cards and monitors meant that it was 1987 before EGA support became common, and 1990 before it hit its stride. Yet EGA helped to spur on the rise and development of the PC RPG, including the legendary SSI ‘Gold Box’ series of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons titles, Wizardry VI: Bane of the Cosmic Forge, Might and Magic II and Ultima II to Ultima V.

It also powered a new wave of better-looking graphical adventures, such as Roberta Williams’ Kings Quest II and III, plus The Colonel’s Bequest. EGA helped LucasArts to bring us pioneering point-and-click classics such as Maniac Mansion and Loom in 16 colours. And while most games stuck to a 320 x 200 resolution, some, such as SimCity, would make the most of the higher 640 x 350 option.

What’s more, EGA made real action games on the PC a realistic proposition. The likes of the Commander Keen games proved the PC could run scrolling 2D platformers properly. You could port over Apple II games such as Prince of Persia, and they wouldn’t be a hideous, four-colour mess.

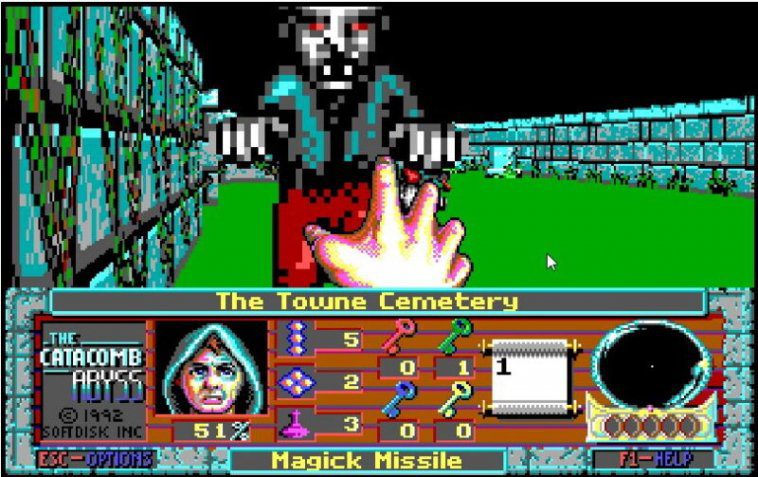

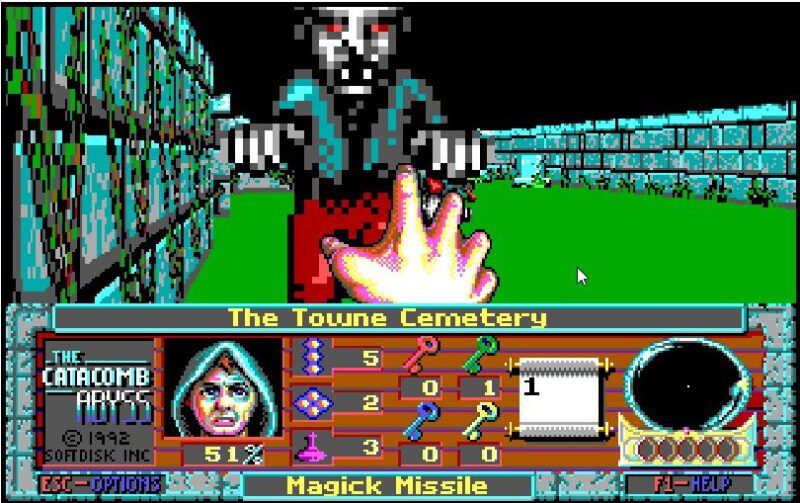

And when the coder behind Commander Keen – a certain John Carmack – started work on a new 3D sequel to the Catacomb series of dungeon crawlers, he created something genuinely transformative. Catacomb 3-D and Catacomb: Abyss gave Carmack his first crack at a texture-mapped 3D engine, and arguably started the FPS genre.

Sure, EGA had its limitations – looking back, there’s an awful lot of green and purple – but with care and creativity, an artist could do a lot with 16 colours and begin creating more immersive game worlds.

A slow decline

EGA’s time at the top of the graphics tech tree was short. Home computers kept evolving, and in 1985, Commodore launched the Amiga, supporting 64 colours in games and up to 4,096 in its special HAM mode. Even as it launched EGA, IBM was talking about a new, high-end board, the Professional Graphics Controller (PGC), which could run screens at 640 x 480 with 256 colours from a total of 4,096.

PGC was priced high and aimed at the professional CAD market, but it helped to pave the way for the later VGA standard, introduced with the IBM PS/2 in 1987. VGA supported the same maximum resolution and up to 256 colours at 320 x 200. This turned out to be exactly what was needed for a new generation of operating systems, applications and PC games.

What extended EGA’s lifespan was the fact that VGA remained expensive until the early 1990s, while EGA had developed a reasonable install base. Even once VGA hit the mainstream, many games remained playable in slightly gruesome 16-colour EGA. Much like the 286 processor and the Ad-Lib sound card, EGA came before the golden age of PC gaming, but this standard paved the way for the good stuff that came next.

The retro tech inspiration behind Raspberry Pi 400

Did you know that Raspberry Pi 400 was inspired by retro tech?

Eben Upton explains:

“Raspberry Pi has always been a PC company. Inspired by the home computers of the 1980s, our mission is to put affordable, high-performance, programmable computers into the hands of people all over the world. And inspired by these classic PCs, here is Raspberry Pi 400: a complete personal computer, built into a compact keyboard… Classic home computers – BBC Micros, ZX Spectrums, Commodore Amigas, and the rest – integrated the motherboard directly into the keyboard. No separate system unit and case; no keyboard cable. Just a computer, a power supply, a monitor cable, and (sometimes) a mouse.”

Download Custom PC for free

Yes, you did read that right. Not only have we unleashed an awesome new issue of Custom PC into the wild, but you can even download a PDF of it for the bargain price of absolutely nothing. In fact, you’ll be able to download every issue of Custom PC over the summer for free.

Website: LINK