If you buy an Android phone, you’re choosing one of the world’s two most popular mobile platforms—one that has expanded the choice of phones available around the world.

Today, the European Commission issued a competition decision against Android, and its business model. The decision ignores the fact that Android phones compete with iOS phones, something that 89 percent of respondents to the Commission’s own market survey confirmed. It also misses just how much choice Android provides to thousands of phone makers and mobile network operators who build and sell Android devices; to millions of app developers around the world who have built their businesses with Android; and billions of consumers who can now afford and use cutting-edge Android smartphones.

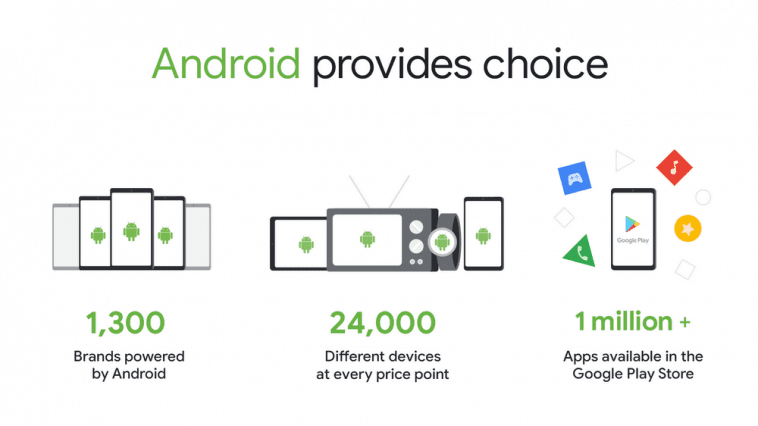

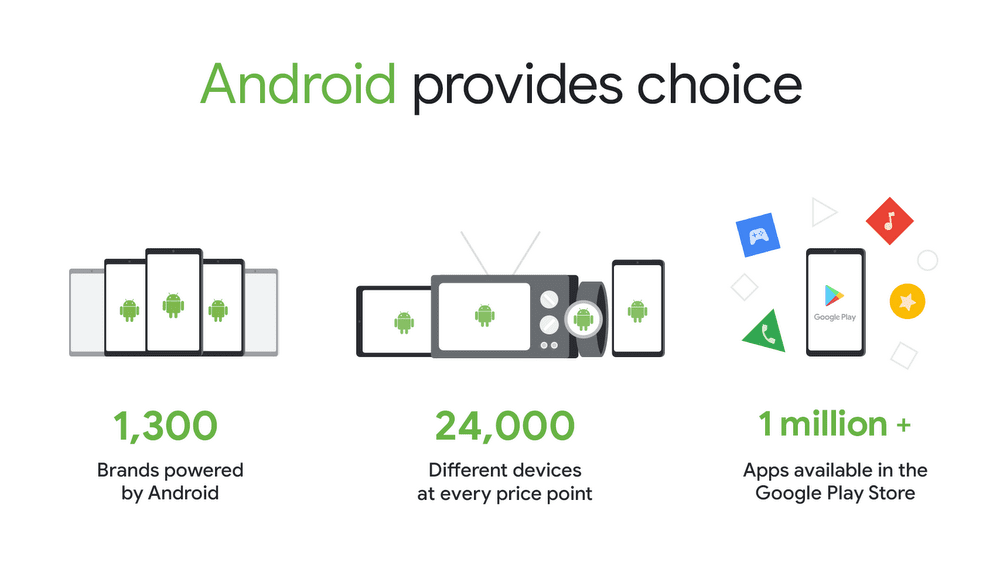

Today, because of Android, there are more than 24,000 devices, at every price point, from more than 1,300 different brands, including Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Latvian, Polish, Romanian, Spanish and Swedish phone makers.

The phones made by these companies are all different, but have one thing in common—the ability to run the same applications. This is possible thanks to simple rules that ensure technical compatibility, no matter what the size or shape of the device. No phone maker is even obliged to sign up to these rules—they can use or modify Android in any way they want, just as Amazon has done with its Fire tablets and TV sticks.

To be successful, open-source platforms have to painstakingly balance the needs of everyone that uses them. History shows that without rules around baseline compatibility, open-source platforms fragment, which hurts users, developers and phone makers. Android’s compatibility rules avoid this, and help make it an attractive long-term proposition for everyone.

Creating flexibility, choice and opportunity

Today, because of Android, a typical phone comes preloaded with as many as 40 apps from multiple developers, not just the company you bought the phone from. If you prefer other apps—or browsers, or search engines—to the preloaded ones, you can easily disable or delete them, and choose other apps instead, including apps made by some of the 1.6 million Europeans who make a living as app developers.

In fact, a typical Android phone user will install around 50 apps themselves. Last year, over 94 billion apps were downloaded globally from our Play app store; browsers such as Opera Mini and Firefox have been downloaded more than 100 million times, UC Browser more than 500 million times.

This is in stark contrast to how things used to be in the 1990s and early 2000s—the dial-up age. Back then, changing the pre-installed applications on your computer, or adding new ones, was technically difficult and time-consuming. The Commission’s Android decision ignores the new breadth of choice and clear evidence about how people use their phones today.

A platform built for the smartphone era

In 2007, we chose to offer Android to phone makers and mobile network operators for free. Of course, there are costs involved in building Android, and Google has invested billions of dollars over the last decade to make Android what it is today. This investment makes sense for us because we can offer phone makers the option of pre-loading a suite of popular Google apps (such as Search, Chrome, Play, Maps and Gmail), some of which generate revenue for us, and all of which help ensure the phone ‘just works’, right out of the box. Phone makers don’t have to include our services; and they’re also free to pre-install competing apps alongside ours. This means that we earn revenue only if our apps are installed, and if people choose to use our apps instead of the rival apps.

Good for partners, good for consumers

The free distribution of the Android platform, and of Google’s suite of applications, is not only efficient for phone makers and operators—it’s of huge benefit for developers and consumers. If phone makers and mobile network operators couldn’t include our apps on their wide range of devices, it would upset the balance of the Android ecosystem. So far, the Android business model has meant that we haven’t had to charge phone makers for our technology, or depend on a tightly controlled distribution model.

We’ve always agreed that with size comes responsibility. A healthy, thriving Android ecosystem is in everyone’s interest, and we’ve shown we’re willing to make changes. But we are concerned that today’s decision will upset the careful balance that we have struck with Android, and that it sends a troubling signal in favor of proprietary systems over open platforms.

Rapid innovation, wide choice, and falling prices are classic hallmarks of robust competition and Android has enabled all of them. Today’s decision rejects the business model that supports Android, which has created more choice for everyone, not less. We intend to appeal.

Rapid innovation, wide choice, and falling prices are classic hallmarks of robust competition and Android has enabled all of them.Website: LINK