It’s easy to let yourself be lured into the 1980s world of Crossing Souls. The striking, Saturday morning cartoon cinematics pull you into an equally enticing pixel-art world, where every little detail is likely something significant from your childhood, at least if you’re over 30 years old. But while there is some satisfaction in the game’s core action, the way it utilizes and adheres to its retro-pop influences ultimately detracts from it in the long run.

Taking its cues from films like The Goonies, Stand By Me, and The Neverending Story, Crossing Souls revolves around a group of five teenagers as they discover an ancient artifact with mystical properties. With some tinkering from the group’s incomprehensibly brilliant genius, they learn that they can cross into the spiritual world and interact with ghosts. Naturally, their discovery draws the attention of a ruthless paramilitary organization who will stop at nothing to obtain the stone for their own nefarious purposes, including harming the children and their families.

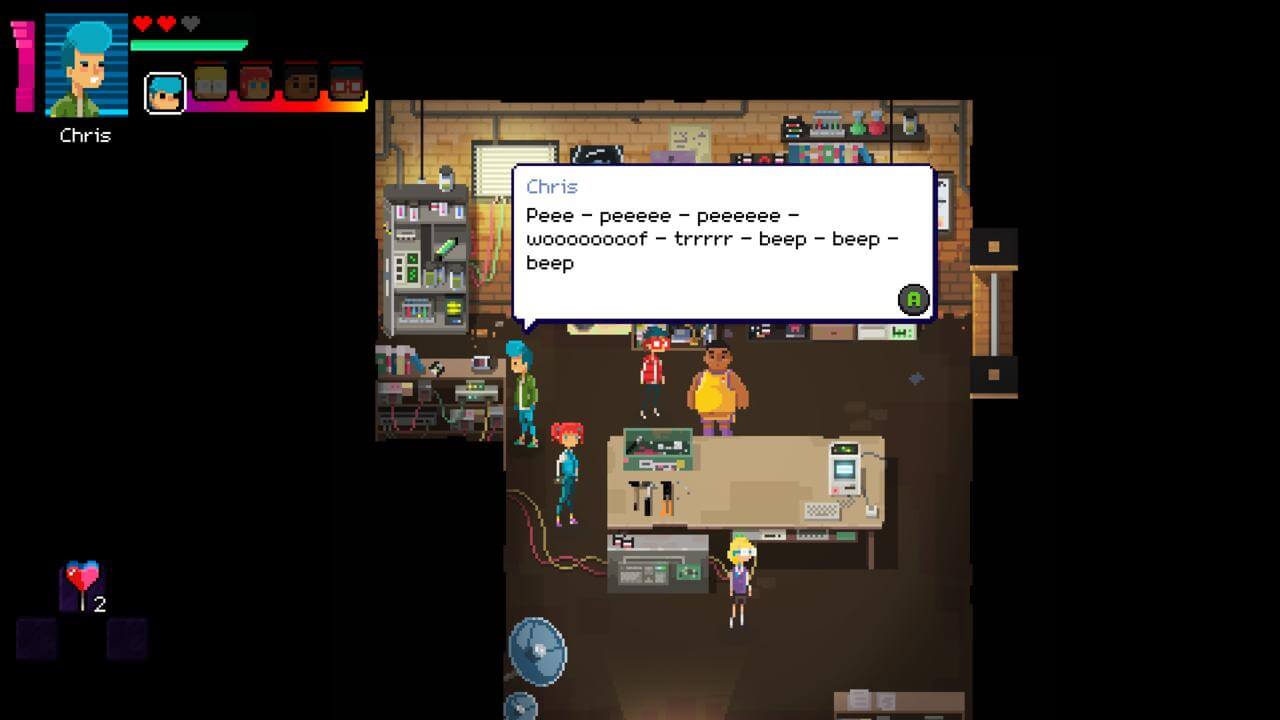

You control all five kids, guiding them through an action-adventure analogous to 2D Zelda games, and regularly switch between them to take advantage of each kid’s unique attack and traversal abilities. Main protagonist Chris is an athletic type who hits things with a baseball bat, aforementioned genius Matt has a deadly ray-gun because he’s smart I guess, „Big“ Joe’s large frame means his punches pack immense damage, Charlie (Charlene) has a skipping rope that provides great crowd control, and Chris‘ kid-brother Kevin can pick his nose, and that’s about it.

Each kid has separate health and stamina bars, but depleting the health of just one means game over. Combat is a juggling act where you might be using the kid whose attack is most suitable for the fight, but also tagging them out when they take too much of a beating or become exhausted. It’s a system that’s surprisingly involved; taking out a group of enemies with a character’s melee combo is easy enough, but you can very quickly become overwhelmed after a couple of whiffed blows or ill-timed dodges. The skills and abilities you have at the beginning of the game are what will carry you all the way through to the end since Crossing Souls eschews ability and equipment upgrades. But although combat isn’t particularly complex, most attacks have satisfying feedback which give fights an enjoyable heft, and encounters are challenging enough to continually keep you on your toes.

Crossing Souls also features some equally demanding environmental puzzles. While simpler variants involve throwing switches, finding keys, and using Big Joe to move boxes, there are also a significant amount of unexpectedly challenging platforming sections where you’ll use Chris‘ unique ability to jump and climb in tandem with Matt’s ability to hover for limited distances, and flip back and forth between the two in quick succession. You eventually also get the ability to cross into the spirit world to phase through doors (although not walls or traffic cones, strangely), which introduces another facet to puzzles. The game’s character movement and perspective isn’t an ideal fit for precision platforming, and some later challenges introduce some downright devious scenarios that verge on aggravating, but even so, completing these puzzles feel like well-earned achievements.

The game seeks to maintain a balance of difficulty which teeters on that precipice of engaging and downright frustrating. But it’s a thin line, and there are a handful of significant sections that feel like they err too much on the wrong side. One particular sequence involves an extensive fetch quest that makes you ping-pong through numerous NPCs to move things along, and then asks you to make a seemingly straightforward deduction. But it felt as if a step was missing, something that could help you deduce the specific location to apply that information, and this completely curbed my enthusiasm until I brute-forced my way through it.

Some boss fights have an overly demanding onslaught of projectiles for you to dodge at length. They’re shoot-‚em-up-style patterns you need to internalize and anticipate with little room for error, and in these scenarios, throwing yourself at it again and again while learning a bit more each time is what will eventually get you through it. But while I personally enjoy these kinds of challenges, Crossing Souls isn’t a game that’s tuned for precise, repeated action. So hitting one of these particularly tough battles, failing it because you’ve been stun-locked by mortar fire, and then having to watch an introductory cutscene again and again is annoying enough to make you walk away.

Outside of regular combat and puzzle-solving, Crossing Souls also weaves in standalone minigame scenarios that are directly based on iconic 1980s film and video games. Sequences that echo Double Dragon, Raiden, and the bike chase in E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial are fun diversions, but these examples represent the extent to which the game leverages its influences in a significantly positive way.

There is plenty to enjoy on a superficial level, of course; the impressive visual style, pixel art in a fashion that echoes The Secret of Monkey Island, is bursting with dozens of small visual references to entertainment products of the era. There are little nods to everything from Nintendo, to Die Hard, to The Land Before Time, to Stephen King, and more substantial set pieces that replicate moments from Stand By Me, Ghostbusters, and Metal Gear. Mousers from the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon appear as late-game enemies, and more modern references from Breaking Bad, Grim Fandango, and Half-Life are also present, seemingly just for the hell of it. But Crossing Souls‘ fervent obsession with its source materials is ultimately its biggest hindrance.

1980s Spielberg adventures and coming-of-age films are the game’s primary touchstones, and while the overarching supernatural adventure in Crossing Souls is uniquely interesting in concept, the character-level experience of it feels strangely empty. Though the story revolves around a group of kids going up against impossible odds, little time is spent exploring any individual child, or even their relationships with one another. You only get a broad outline, reliant on archetypes like the athletic white kid, the dweeby nerd, the fat kid, and the girl. There is no nuance in their personalities, so when a character has a sudden change of attitude, it feels like it comes entirely out of left field. When something utterly drastic happens, it doesn’t really worry you. Though the story takes the stakes to some pretty wild extremes, Crossing Souls doesn’t do enough to convince you that this band of kids actually cares enough to protect one another against the cartoonishly evil villains. The multiple antagonists are equally as shallow, with no real defining features aside from their ruthlessness; stereotypes are their primary traits.

In-depth character development supposedly takes a backseat to the density of nostalgic callbacks. An elongated sequence, mentioned earlier, is based on Back To The Future III and culminates in a Track & Field-style minigame to boost the speed of a DeLorean. But the entire section is inconsequential, having no real impact on any of the plot events that precede or follow it. And when you get a joke about the fat kid shitting his pants for the third time, you begin to wonder whether these spaces and lines of dialogue could have been better utilized.

Its strict adherence to familiar tropes also means that Crossing Souls adopts some of the more dubious traditions of 1980s pop cinema. An elderly, mystic Asian shopkeeper echoes the House of Evil shopkeeper in The Simpsons and Lo Pan in Big Trouble in Little China, but it’s a caricature that comes off as crass and half-baked–the game can’t even seem to decide whether he speaks fluent or broken English. This shopkeeper, along with Big Joe, his mother, and a Prince look-alike, are seemingly the only people of color in a Californian town filled with dozens of visible NPCs. There are jokes made at the expense of a community of rednecks, forever dumb and drunk. Charlie, who hails from this group, is abruptly reduced to a damsel and love interest despite being one of the more combat-useful characters with a fierce personality archetype. Replicating these familiar tropes and caricatures from 1980s cinema may serve as an homage, but they feel dated and detract from what could have been a more meaningful adventure.

Crossing Souls has the building blocks of a rousing ’80s adventure. Experiencing the significant, pitch-perfect moments of the story is great, because it’s hard not to get energized by a John Williams-esque score, or get a little sentimental as the credits roll over a feelgood synthpop track. But when you emerge from the nostalgia-induced stupor, it’s hard to deny that the characters and plot that underpin it all could definitely be more substantial. Crossing Souls has good mechanics, and its facade is a visual treat that is easy to be seduced by, but it fails to achieve a level of holistic enjoyment that raises it past the giant pile of references.

Website: LINK