Improving gender balance in computing is part of our work to ensure equitable learning opportunities for all young people. Our Gender Balance in Computing (GBIC) research programme has been the largest effort to date to explore ways to encourage more girls and young women to engage with Computing.

Commissioned by the Department for Education in England and led by the Raspberry Pi Foundation as part of our National Centre for Computing Education work, the GBIC programme was a collaborative effort involving the Behavioural Insights Team, Apps for Good, and the WISE Campaign.

Gender Balance in Computing ran from 2019 to 2022 and comprised seven studies relating to five different research areas:

- Teaching Approach:

- Belonging: Supporting learners to feel that they “belong” in computer science

- Non-formal Learning: Establishing the connections between in-school and out-of-school computing

- Relevance: Making computing relatable to everyday life

- Subject Choice: How computer science is presented to young people as a subject choice

In December we published the last of seven reports describing the results of the programme. In this blog post I summarise our overall findings and reflect on what we’ve learned through doing this research.

Gender balance in computing is not a new problem

I was fascinated to read a paper by Deborah Butler from 2000 which starts by summarising themes from research into gender balance in computing from the 1980s and 1990s, for example that boys may have access to more role models in computing and may receive more encouragement to pursue the subject, and that software may be developed with a bias towards interests traditionally considered to be male. Butler’s paper summarises research from at least two decades ago — have we really made progress?

In England, it’s true that making Computing a mandatory subject from age 5 means we have taken great strides forward; the need for young people to make a choice about studying the subject only arises at age 14. However, statistics for England’s externally assessed high-stakes Computer Science courses taken at ages 14–16 (GCSE) and 16–18 (A level) clearly show that, although there is a small upwards trend in the proportion of female students, particularly for A level, gender balance among the students achieving GCSE/A level qualifications remains an issue:

| Computer Science qualification (England): | In 2018: | In 2021: | In 2022: |

| GCSE (age 16) | 20.41% | 20.77% | 21.37% |

| A level (age 18) | 11.74% | 14.71% | 15.17% |

What did we do in the Gender Balance in Computing programme?

In GBIC, we carried out a range of research studies involving more than 14,500 pupils and 725 teachers in England. Implementation teams came from the Foundation, Apps For Good, the WISE Campaign, and the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT). A separate team at BIT acted as the independent evaluators of all the studies.

In total we conducted the following studies:

- Two feasibility studies: Storytelling; Relevance, which led to a full randomised controlled trial (RCT)

- Five RCTs: Belonging; Peer Instruction; Pair Programming; Relevance, which was preceded by a feasibility study; Non-formal Learning (primary)

- One quasi-experimental study: Non-formal Learning (secondary)

- One exploratory research study: Subject Choice (Subject choice evenings and option booklets)

Each study (apart from the exploratory research study) involved a 12-week intervention in schools. Bespoke materials were developed for all the studies, and teachers received training on how to deliver the intervention they were a part of. For the RCTs, randomisation was done at school level: schools were randomly divided into treatment and control groups. The independent evaluators collected both quantitative and qualitative data to ensure that we gained comprehensive insights from the schools’ experiences of the interventions. The evaluators’ reports and our associated blog posts give full details of each study.

The impact of the pandemic

The research programme ran from 2019 to 2022, and as it was based in schools, we faced a lot of challenges due to the coronavirus pandemic. Many research programmes meant to take place in school were cancelled as soon as schools shut during the pandemic.

Although we were fortunate that GBIC was allowed to continue, we were not allowed to extend the end date of the programme. Thus our studies were compressed into the period after schools reopened and primarily delivered in the academic year 2021/2022. When schools were open again, the implementation of the studies was affected by teacher and pupil absences, and by schools necessarily focusing on making up some of the lost time for learning.

The overall results of Gender Balance in Computing

Quantitatively, none of the RCTs showed a statistically significant impact on the primary outcome measured, which was different in different trials but related to either learners’ attitudes to computer science or their intention to study computer science. Most of the RCTs showed a positive impact that fell just short of statistical significance. The evaluators went to great lengths to control for pandemic-related attrition, and the implementation teams worked hard to support teachers in still delivering the interventions as designed, but attrition and disruptions due to the pandemic may have played a part in the results.

The qualitative research results were more encouraging. Teachers were enthusiastic about the approaches we had chosen in order to address known barriers to gender balance, and the qualitative data indicated that pupils reacted positively to the interventions. One key theme across the Teaching Approach (and other) studies was that girls valued collaboration and teamwork. The data also offered insights that enable us to improve on the interventions.

We designed the studies so they could act as pilots that may be rolled out at a national scale. While we have gained sufficient understanding of what works to be able to run the interventions at a larger scale, two particular learnings shape our view of what a large-scale study should look like:

1. A single intervention may not be enough to have an impact

The GBIC results highlight that there is no quick fix and suggest that we should combine some of the approaches we’ve been trialling to provide a more holistic approach to teaching Computing in an equitable way. We would recommend that schools adopt several of the approaches we’ve tested; the materials associated with each intervention are freely available (see our blog posts for links).

2. Age matters

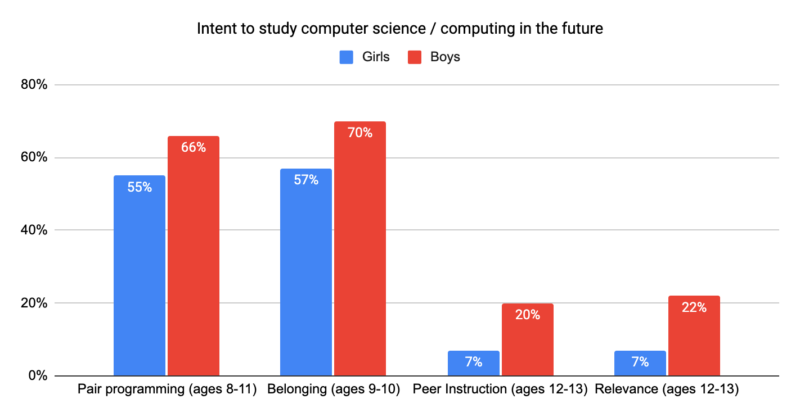

One of the very interesting overall findings from this research programme was the difference in intent to study Computing between primary school and secondary school learners; fewer secondary school learners reported intent to study the subject further. This difference was observed for both girls and boys, but was more marked for girls, as shown in the graph below. This suggests that we need to double down on supporting children, especially girls, to maintain their interest in Computing as they enter secondary school at age 11. It also points to a need for more longitudinal research to understand more about the transition period from primary to secondary school and how it impacts children’s engagement with computer science and technology in general.

What’s next?

We think that more time (in excess of 12 weeks) is needed to both deliver the interventions and measure their outcome, as the change in learners’ attitudes may be slow to appear, and we’re hoping to engage in more longitudinal research moving forward.

We know that an understanding of computer science can improve young people’s access to highly skilled jobs involving technology and their understanding of societal issues, and we need that to be available to all. However, gender balance relating to computing and technology is a deeply structural issue that has existed for decades throughout the computing education and workplace ecosystem. That’s why we intend to pursue more work around a holistic approach to improving gender balance, aligning with our ongoing research into making computing education culturally relevant.

Stay in touch

We are very keen to continue to build on our research on gender balance in computing. If you’d like to support us in any way, we’d love to hear from you. To explore the research projects we’re currently involved in, check out our research pages and visit the website of the Raspberry Pi Computing Education Research Centre at the University of Cambridge.

Website: LINK