Around the world, formal education systems are bringing computing knowledge to learners. But what exactly is set down in different countries’ computing curricula, and what are classroom educators teaching? This was the topic of the first in the autumn series of our Raspberry Pi research seminars on Tuesday 8 September.

We heard from an international team (Monica McGill , USA; Rebecca Vivian, Australia; Elizabeth Cole, Scotland) who represented a group of researchers also based in England, Malta, Ireland, and Italy. As a researcher working at the Raspberry Pi Foundation, I myself was part of this research group. The group developed METRECC, a comprehensive and validated survey tool that can be used to benchmark and measure developments of the teaching and learning of computing in formal education systems around the world. Monica, Rebecca, and Elizabeth presented how the research group developed and validated the METRECC tool, and shared some findings from their pilot study.

What’s in a curriculum? Developing a survey tool

Those of us who work or have worked in school education use the word ‘curriculum’ frequently, although it’s an example of education terminology that means different things in different contexts, and to different people. Following Porter and Smithson (2001)1, we can distinguish between the intended curriculum and the enacted curriculum:

- Intended curriculum: Policy tools as curriculum standards, frameworks, or guidelines that outline the curriculum teachers are expected to deliver.

- Enacted curriculum: Actual curricular content in which students engage in the classroom, and adopted pedagogical approaches; for computer science (CS) curricula, this also includes students’ use of technology, physical computing devices, and tools in CS lessons.

To compare the intended and enacted computing curriculum in as many countries as possible, at particular points in time, the research group Monica, Rebecca, Elizabeth, and I were part of developed the METRECC survey tool.

METRECC stands for MEasuring TeacheREnacted Computing Curriculum. The METRECC survey has 11 categories of questions and is designed to be completed by computing teachers within 35–40 minutes. Following best practice in research, which calls for standardised research instruments, the research group ensured that the survey produces valid, reliable results (meaning that it works as intended) before using it to gather data.

Using METRECC in a pilot study

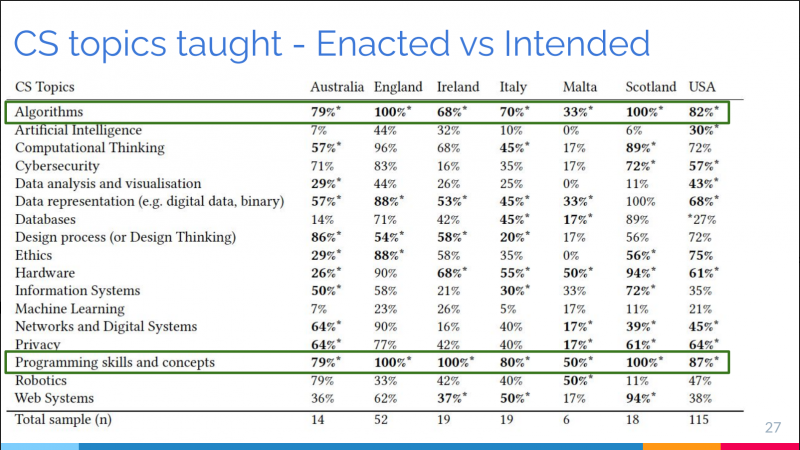

In their pilot study, the research group gathered data from 7 countries. The intended curriculum for each country was determined by examining standards and policies in place for each country/state under consideration. Teachers’ answers in the METRECC survey provided the countries’ enacted curricula. (The complete dataset from the pilot study is publicly available at csedresearch.org, a very useful site for CS education researchers where many surveys are shared.)

The researchers then mapped the intended to the enacted curricula to find out whether teachers were actually teaching the topics that were prescribed for them. Overall, the results of the mapping showed that there was a good match between intended and enacted curricula. Examples of mismatches include lower numbers of primary school teachers reporting that they taught visual or symbolic programming, even though the topic did appear on their curriculum.

Another aspect of the METRECC survey allows to measure teachers’ confidence, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. The results of the pilot study showed a relationship between years of experience and CS self-esteem; in particular, after four years of teaching, teachers started to report high self-esteem in relation to computer science. Moreover, primary teachers reported significantly lower self-esteem than secondary teachers did, and female teachers reported lower self-esteem than male teachers did.

Adapting the survey’s language

The METRECC survey has also been used in South Asia, namely Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (where computing is taught under ICT). Amongst other things, what the researchers learned from that study was that some of the survey questions needed to be adapted to be relevant to these countries. For example, while in the UK we use the word ‘gifted’ to mean ‘high-attaining’, in the South Asian countries involved in the study, to be ‘gifted’ means having special needs.

The study highlighted how important it is to ensure that surveys intended for an international audience use terminology and references that are pertinent to many countries, or that the survey language is adapted in order to make sense in each context it is delivered.

Let’s keep this monitoring of computing education moving forward!

The seminar presentation was well received, and because we now hold our seminars for 90 minutes instead of an hour, we had more time for questions and answers.

My three main take-aways from the seminar were:

1. International collaboration is key

It is very valuable to be able to form international working groups of researchers collaborating on a common project; we have so much to learn from each other. Our Raspberry Pi research seminars attract educators and researchers from many different parts of the world, and we can truly push the field’s understanding forward when we listen to experiences and lessons of people from diverse contexts and cultures.

2. Making research data publicly available

Increasingly, it is expected that research datasets are made available in publicly accessible repositories. While this is becoming the norm in healthcare and scientific, it’s not yet as prevalent in computing education research. It was great to be able to publicly share the dataset from the METRECC pilot study, and we encourage other researchers in this field to do the same.

3. Extending the global scope of this research

Finally, this work is only just beginning. Over the last decade, there has been an increasing move towards teaching aspects of computer science in school in many countries around the world, and being able to measure change and progress is important. Only a handful of countries were involved in the pilot study, and it would be great to see this research extend to more countries, with larger numbers of teachers involved, so that we can really understand the global picture of formal computing education. Budding research students, take heed!

Next up in our seminar series

If you missed the seminar, you can find the presentation slides and a recording of the researchers’ talk on our seminars page.

In our next seminar on Tuesday 6 October at 17:00–18:30 BST / 12:00–13:30 EDT / 9:00–10:30 PT / 18:00–19:30 CEST, we’ll welcome Shuchi Grover, a prominent researcher in the area of computational thinking and formative assessment. The title of Shuchi’s seminar is Assessments to improve student learning in introductory CS classrooms. To join, simply sign up with your name and email address.

Once you’ve signed up, we’ll email you the seminar meeting link and instructions for joining. If you attended this past seminar, the link remains the same.

1. Andrew C. Porter and John L. Smithson. 2001. Defining, Developing and Using Curriculum Indicators. CPRE Research Reports, 12-2001. (2001)

Website: LINK